| Climb Up or Dig Down: Reflections on the Capstone Course in a Religious Studies MA Program - The Rhizome as an Alternative to the Capstone |

![PDF-NOTE: Internet Explorer Users, right click the PDF Icon and choose [save target as] if you are experiencing problems with clicking.](http://rsnonline.org/templates/rsntemplate-smallmasthead/images/pdf_button.png) |

|

|

Page 2 of 3

Rethinking the capstone began for me as an exercise in metaphor and departmental realities rather than pedagogical theory. The architectural metaphor of the capstone describes well the advantages of a traditional capstone course. The metaphor imagines a program as vertical architecture, typically with a required first-semester course acting as a “cornerstone” supporting the above structure of lecture-based and seminar courses that students “climb,” gaining intellectual altitude as they move upward. Reaching the top, the capstone of the structure, students survey their ascent by producing projects that have critically integrated the descriptive data and analytical skill sets learned along the climb. The metaphor suggests positive qualities — the necessity of foundational knowledge, intellectual mentoring, sharing in a disciplinary discourse, and growing intellectual independence. The capstone, as the pedagogical literature agrees, is also a better gauge for learning assessment than the exam model, which typically can measure only the retention and organization of information. When this metaphor meets the reality of a small religious studies department, however, potential problems inherent within the traditional capstone are exposed. Thinking through metaphor and departmental realities has convinced me, in ways I have not seen addressed in the literature, that no one size capstone model can fit all, and that any capstone must develop out of the strengths and unique composition of a department’s faculty. Given religious studies’ theological origins and interdisciplinary nature, a department of religious studies that possesses faculty trained in various fields is more the rule than the exception. Rarely are religious studies scholars the sole inhabitants of their departments, despite the eponymous term. In addition to those with degrees in religious studies, biblical scholars trained in divinity schools or departments of theology and area studies — specialists with deep historical knowledge of select cultural regions (and where religion is just one focus to which they are attentive) — typically fill out the faculty roster, though specialists from other disciplines may also be on the faculty. Such hybridity fits awkwardly with the capstone experience as the above metaphor evokes it. If the course is to cap a career of disciplinary-specific study, then this becomes, shall we say, a difficult climb given the multiplicity of disciplines that may mark faculty training. This is most apparent in tasking the capstone’s instructor with fulfilling the objectives of the course. A biblicist or a regionalist, while possessing research and teaching strength in textual analysis or area history, may not have broad familiarity with classical and contemporary issues of theory and methodology that have come to comprise much of the discourse of disciplinary identity within religious studies. In a small department, consequently, the number of instructors available to head such a capstone course may be limited. That number may be further squeezed given, on the one hand, the demands of undergraduate teaching, and on the other hand, reluctance of some faculty members to sacrifice part of their teaching repertoire for a capstone. This can lead to a double-sided situation of course inequity and course monopolization. Course inequity — where some faculty members accept the burden of the capstone while others remain free of it — may lead to course monopolization — where sometimes one “burdened” instructor for years effectively becomes gatekeeper to the course, placing his or her sole imprimatur on what it means to be a scholar of religion.

|

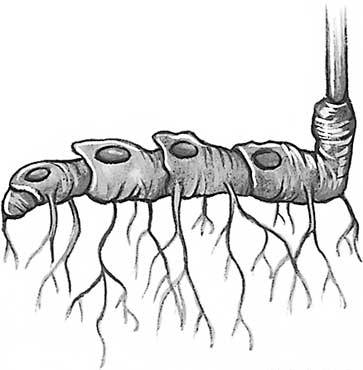

An alternative to the traditional capstone needs to be created within such realities, so that the hybridity of faculty strengthens rather than complicates the task, and that more, rather than fewer, instructors participate and offer their unique fields of training to the students in sustained projects. This suggests a different metaphor that moves away from the capstone’s stress on verticality and singularity and toward horizontality and multiplicity. More to the metaphorical point, rather than the imagery of a fixed single building, the contrasting imagery of a rhizome offers an alternative to thinking about the capstone. Rather than ascending to the top of a pyramid to cap one’s education through a single course, the rhizome metaphor encourages a different type of intellectual movement. Students do not climb up but dig down, root around to harvest from one plant multiple tubers, and, as this metaphor implies, expand and deepen their methodological and interpretative skill sets through multiple, similarly structured courses and mentorships with faculty.

An alternative to the traditional capstone needs to be created within such realities, so that the hybridity of faculty strengthens rather than complicates the task, and that more, rather than fewer, instructors participate and offer their unique fields of training to the students in sustained projects. This suggests a different metaphor that moves away from the capstone’s stress on verticality and singularity and toward horizontality and multiplicity. More to the metaphorical point, rather than the imagery of a fixed single building, the contrasting imagery of a rhizome offers an alternative to thinking about the capstone. Rather than ascending to the top of a pyramid to cap one’s education through a single course, the rhizome metaphor encourages a different type of intellectual movement. Students do not climb up but dig down, root around to harvest from one plant multiple tubers, and, as this metaphor implies, expand and deepen their methodological and interpretative skill sets through multiple, similarly structured courses and mentorships with faculty.