| Critical Thinking and Prophetic Witness, Historically–Theologically Based |

![PDF-NOTE: Internet Explorer Users, right click the PDF Icon and choose [save target as] if you are experiencing problems with clicking.](http://rsnonline.org/templates/rsntemplate-smallmasthead/images/pdf_button.png) |

|

Glen H. Stassen, Fuller Theological Seminary

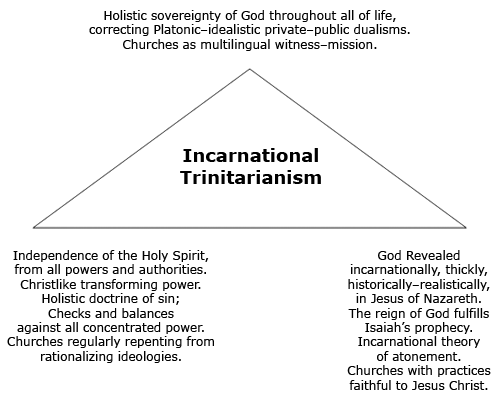

In our time of pluralistic encounter with multiple ideologies and faiths, people search for what Bonhoeffer called ground to stand on. Fearing we are losing our grounding leads some to reactionary authoritarianism, with its militarism and nationalism, that my ancestors left pre-fascist Germany to get away from, and that we see now in the religious right, and in al Qaeda. We need to help students find ground to stand on with normative richness, but without being authoritarian. Though I was influenced from the start by H. Richard Niebuhr’s wrestle with historical relativism and so was a postmodernist before the term was invented, criticizing the Enlightenment’s “universalistic” rationalism from my dissertation on, my identification with Bonhoeffer and the Confessing Church Struggle gives me the willies when I see some doing their ethics in pure reaction against the Enlightenment — as pre-fascist philosophers in Germany did (Stern 1974). In reaction they threw out contributions of free-church Puritanism — the right to religious liberty, human rights, and democracy — because the Enlightenment later affirmed them. They lusted for homogeneous community — which requires authoritarianism to maintain. Though my loyalties and experiences make me an opponent of authoritarianism and racism deep, deep down, I do not want students to do their ethics so in reaction against authority that they dissolve faith into privatistic normlessness, situationism, freedom as individualistic autonomy, avant-gardism, or inward emigration out of covenant responsibility for the common good. I share with many feminists a criticism of Enlightenment rationalism, but also a need for transcultural norms of justice with which to criticize power structures and status quo ideologies. But how shall we ground an ethic that is neither authoritarian nor merely subjective? In our time, when students are aware that we are all shaped by our history, “where we are coming from,” validation works best by historical testing. We cannot claim a universal location above history, but we can assess the historical fruits of ethics people have lived by. I adopt H. Richard Niebuhr’s advocacy of “history as the laboratory in which our faith is tested.” In Kingdom of God in America, Niebuhr looked for times of prophetic lava flow when American churches didn’t merely accommodate to social forces, but were authentically transformationist: early Puritanism before it cooled into defensiveness, the Great Awakenings, and the social gospel. We can carry his method further by examining times of testing when most all agree who passed the historical test. The Third Reich is one such time. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Karl Barth, and André Trocmé came through. In Righteous Gentiles of the Holocaust, David Gushee studied those who rescued Jews while others were bystanders or Hitler–supporters. Parush Parushev’s dissertation studies the faith of those who led Bulgaria to rescue all their Jews (2005). Another such time of testing is the U.S. civil rights movement. In “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Martin Luther King Jr. challenges those white church leaders who sat on the sidelines. Even some black church leaders had an otherworldly faith, or were too beholden to the power structures to support the movement. In his Beloved Community: How Faith Shapes Social Justice, Charles Marsh shows King and others coming through, and also white Southern Baptist Clarence Jordan, and more recently John Perkins (2005). Johannes Hamel, Albrecht Schönherr, and others came through during the Revolution of the Candles that toppled East German dictator Eric Honecker, and the Wall, completely nonviolently. The leaders of that movement were disciples of Bonhoeffer and Barth. Similarly, Dorothy Day, Muriel Lester, Ronald Sider, and Jim Wallis have passed the test in the face of ideologies that support economic injustice. I am struck that those who passed these historical tests had the three themes in their faith that I call “incarnational trinitarianism” (Stassen, Yeager, and Yoder 1996). Three caveats: 1) “Incarnational trinitarianism” is not merely an affirmation of the doctrine of the Trinity. Many affirm that doctrine, but fail the test of history. 2) H. Richard Niebuhr experienced a major problem in his theology in the 1950s; his writing then lacked a crucial dimension of incarnational trinitarianism, and his prophetic edge weakened strikingly — but temporarily (Stassen, Yeager, and Yoder 1996). 3) In Righteous Gentiles, Gushee concludes that social influences and personal propensities are not a sufficient explanation; we need attention to the theological-ethical content of their faith to understand how these heroes of the faith came through. My own study of the other test periods leads me to concur. Incarnational TrinitarianismIn my course on Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s theological ethics, we contrast Martin Doblemeier’s film, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, with “Theologians under Hitler,” (available from Steven D. Martin at This e-mail address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it ). Then students perform a readers’ theater I wrote, asking “Why did Bonhoeffer stand up, when others ducked their responsibility?” The Incarnate Jesus Concretely Interpreted: Bonhoeffer had strong and specific norms from the incarnate Jesus in the early days when he made the crucial decision to oppose Hitler. He said the Sermon on the Mount converted him from being merely a theologian to being a Christian, and is the only ground strong enough to stand on against Hitler. In Discipleship, he interprets the Sermon on the Mount with a concrete hermeneutics yielding a thick ethic with specific guidance. As John Howard Yoder has written, the Trinity teaches that the real God is revealed concretely in the way of the incarnate Jesus (2002). Barth, Bonhoeffer, Trocmé, Day, Lester, Wallis, and Sider all have a concrete hermeneutic of Jesus’s way (Gushee and Stassen). The Holy Spirit and Continuous Repentance: Bonhoeffer involved himself in an African-American Baptist church in Harlem, in dialogues with French pacifist Jean Lassere, and in the world church. He learned to distinguish Christian loyalty sharply from nationalism, as does the Barmen Confession. All the “saints of the faith” who came through are clear that God is independent from, and calls us to repentance for, our captivity to the assumptions of our society and the powers and authorities of our nation. The Barmen Confession connects God’s call for repentance with the Holy Spirit. Similarly, at Pentecost, Peter called on people to “repent and be baptized, every one of you, in the name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of your sins. And you will receive the gift of the Holy Spirit: The promise is for you and your children and for all who are far off — for all whom the Lord will call.” The Book of Acts is the narrative of the Holy Spirit’s calling the early church to repent for a narrow and nationalistic faith and to recognize the Spirit’s presence to all who are far off — Samaritans, an Ethiopian eunuch, and even Gentiles ignorant of the faith of Israel, so the gospel would be unhindered by narrow loyalties. The Sovereignty of God or Lordship of Christ through All of Life: Bonhoeffer worked out a new political ethic: Christ is Lord over public life as well as over private life. The powers and authorities were created in and through Christ (Colossians 1:15) and have their mandate to rule under Christ. As the Barmen Confession says: “We reject the false doctrine, as though there were areas of our life in which we would not belong to Jesus Christ, but to other Lords....” By contrast, the German churches that succumbed to Hitler’s pressures had previously rejected human rights and the democracy of the Weimar Republic as in a sphere outside Christian concern, and had adopted a pseudo-Lutheran two-realm dualism. Similarly, during slavery times many of my fellow Baptists, whose tradition had been Calvinism with Anabaptist influence, with the sovereignty of God over all of life, adopted a pseudo-Lutheran dualism, declaring that Galatians 3:28 (“There is no longer slave or free, but all are one in Christ”) deals only with spiritual issues, and does not apply to slavery. The emphasis on a holistic ethic in which the Lordship of Christ applies to all of life runs through those who stood the historical test. For example, Martin Luther King’s faith grew from a perception of a passive, individualistic Jesus to Jesus’s way in nonviolent direct action, as can be seen with King’s stance on economic justice, and illustrated in his Riverside Church sermon opposing the Vietnam War. Jeff Stout and Cornel West accept the argument of Stanley Hauerwas and Alasdair MacIntyre that we need to work in a tradition, but argue for a democratic tradition — with contributions from philosophical pragmatism or Socratic self-questioning. I stand with West as he adds African-American tradition and the contribution of the Free-church Puritans to democratic tradition. These fit the Barmen-like tradition that has proved itself in the laboratory of history. In my courses, I diagram incarnational trinitarianism (not all of which I can explain in this short space):

BibliographyGushee, David. Righteous Gentiles of the Holocaust. Fortress Press, 1994. Gushee, David, and Glen Stassen. Kingdom Ethics: Following Jesus in Contemporary Context. InterVarsity, 2003. Parushev, Parush. Walking in the Dawn of the Light. Fuller Theological Seminary, 2006. Marsh, Charles. Beloved Community: How Faith Shapes Social Justice. Basic Books, 2005. Niebuhr, Richard. The Kingdom of God in America. Wesleyan University Press, 1988. Stassen, Glen H., D. M. Yeager, and John Howard Yoder. Authentic Transformation: A New Vision of Christ and Culture. Abingdon, 1996. Stern, Fritz R. The Politics of Cultural Despair: A Study in the Rise of Germanic Ideology. University of California Press, 1974. Stout, Jeffrey. Democracy and Tradition. Princeton University Press, 2004. West, Cornel. Democracy Matters. Penguin, 2004. Yoder, John Howard. Preface to Theology: Christology and Theological Method. Brazos, 2002. |

Glen Stassen is Lewis B. Smedes Professor of Christian Ethics at Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, where he won the All Seminary Council Faculty Award for Outstanding Community Service to Students. He is author of numerous publications, including Living the Sermon on the Mount (Jossey-Bass, 2006) and Kingdom Ethics: Following Jesus in Contemporary Context, with David Gushee (InterVarsity, 2003), which won the Christianity Today Award for Best Book of 2004 in Theology or Ethics. Contact:

Glen Stassen is Lewis B. Smedes Professor of Christian Ethics at Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, where he won the All Seminary Council Faculty Award for Outstanding Community Service to Students. He is author of numerous publications, including Living the Sermon on the Mount (Jossey-Bass, 2006) and Kingdom Ethics: Following Jesus in Contemporary Context, with David Gushee (InterVarsity, 2003), which won the Christianity Today Award for Best Book of 2004 in Theology or Ethics. Contact: