| Teaching Religion and Material Culture |

![PDF-NOTE: Internet Explorer Users, right click the PDF Icon and choose [save target as] if you are experiencing problems with clicking.](http://rsnonline.org/templates/rsntemplate-smallmasthead/images/pdf_button.png) |

|

Vivian-Lee Nyitray

As an undergraduate student at Syracuse University in the early 1970s, I had the great good fortune to enroll in several courses taught by H. Daniel Smith. A consummate teacher, he fostered in me (and countless others, without doubt) a lifelong fascination not just with “religion,” but with the intellectual, emotional, and material totality of religious worlds. What Smith realized was that a student’s interest and attention span is fickle and fleeting — even in those pre-MTV days. To capture it, an instructor’s material had to be vital, and it had to appeal to more than our intellectual curiosity. We had to be fully engaged with the subject. We were thus unprepared for our initial class “meeting”: the classroom was closed and dark, and a sign instructed us to report to the language lab and to request a particular item, which turned out to be a tape-slide combination. As we viewed the first slide — a shot of Professor Smith’s smiling face — we heard a man’s voice on the tape welcome us to the course on Asian religious classics. As this genial voice then guided us through the course manual, we saw illustrations drawn from the texts we’d be reading, saw photographs of sites relevant to the texts, and we listened to music, chant, and liturgy. Clearly, this would be — and was — a class like no other.

Since then, although trained in the textual study of classical Chinese traditions, I have nonetheless come to practice the study of religion in a manner significantly influenced by anthropology, ethnography, art history, and archaeology. Perhaps not unlike other fields, the study of Chinese religions has long been divided into several camps: the historical-philosophical textualists, the anthropologists, and the art historians. The art historians were always in a class by themselves, but between the philosophers and the ethnographers, well, it was clear who claimed the superior discipline! Scholars whose “serious” textual work was paralleled by observations on paper goods, food offerings, or other “popular” artifacts were sometimes treated lightly in years past. Recently, however, the historical, aesthetic, and ethnographic value of their collections has become obvious, and their publications on popular belief and practice are important source materials in their own right. Confucian traditions, for example, establish the family as the locus of religious identity, and thus the study of traditional Chinese homes — their construction and orientation, their furnishings and adornment — now seems a natural subject for investigation. Even Buddhism, a tradition that rejects the material world as so much “dust,” nonetheless has been responsible for the production of a vast array of material goods, all of which provide significant keys to the interpretation of the tradition over time and across geographic space. Most importantly, the new consideration of materiality in Chinese traditions has facilitated conversations among scholars of diverse training and methodological orientation. Scholars of the religions of indigenous peoples worldwide would find none of this new or unusual. They have long been at the forefront of material cultural studies, examining the ways in which textiles, food, architecture, personal adornment, music, dance, and the production of implements all reveal aspects of a particular religious worldview and its associated practices. Some of this focus was prompted initially by the perceived paucity or absence of the classic subject and/or object of study in religion, texts or scriptures. Doctrinal discourses were then discerned in oral tradition, and also in the overarching “narrative” of daily life. Belatedly but happily, these insights have now come into the analysis of other religious traditions, notably the study of Christianity in general and its American variations in particular. In this issue of Spotlight on Teaching, a sampling of scholars and students share their diverse experiences in mediating material culture in the religious studies classroom. An instructor desirous of shifting pedagogical attention beyond words on a page might reasonably turn the classroom gaze toward other aspects of the page, namely, photographs and illustrations — an entry to the field of visual culture. Recent scholarship on the relationship between visual culture and religion reveals much about the role that images play, not only in the imagination or in ritual implementation, but in the material reality of everyday religious life as well. Textual narratives also pave the way for consideration of visual narratives in media as discrete as architecture and film. Contributor Judith Weisenfeld encourages her students to move between the realms of visual and material culture in her course on American religion and film; in addition to screening films for discussion, she also directs student attention to the study of published catalogs and movie memorabilia.

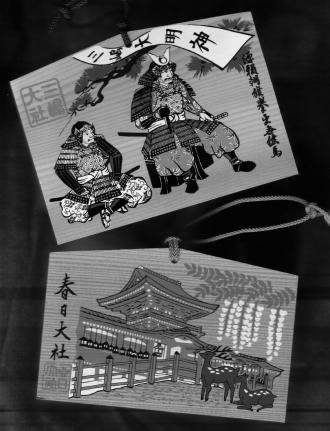

One might also bring the outside world into the classroom. Contributor Leslie Smith recalls a guest practitioner: a Wiccan who, in her choice of clothing and in the artifacts of The Craft that she brought along for the students’ examination, taught volumes about her tradition, about the local community “shared” by everyone present, and about the craft of teaching as well. But bringing the material culture of religion into the classroom carries certain challenges with it. Strenski asks, “Who lugs this stuff to class?” The answer is: I do, for one. I am the bag lady of Religious Studies. In addition to the music tapes and CDs that I carry to class for aural illustration, I bring Hindu and Buddhist images, Chinese paper funerary goods, Tibetan prayer flags, Soka Gakkai bumper stickers, Taoist merit books, and posters depicting everything from highly unpleasant Hindu hells to the Chinese sea goddess Mazu hovering protectively over pleasure craft out for a day’s sail. I bring slides and videos as well, but, as Smith’s essay documents, the physical presence of actual objects is often supremely catalytic for class discussion. Tactile teaching was a staple of our own early childhood education, introducing us to new worlds of experience; why now do we abandon it, particularly in “introductory” courses? Introductions come through a variety of media. The Spring 2001 issue of Spotlight on Teaching focused on aurality, in the form of music, in the classroom. In the current issue, contributor Daniel Sack focuses on a material aspect of orality — discussing the uses of food and notions of eating in teaching the material culture of religion. Through the study of this most basic human activity, Sack illustrates the multiple perspectives students gain into the social and doctrinal assumptions of a religious tradition and its institutions. The importance of treating food, textiles, toys, music, and so forth is also asserted by Strenski: “Material religious culture is composed of all the sensate entities and events of religion.” I would add that an overlooked aspect of these entities and events is their interlocking nature. For example, in a study of radio and religion in Appalachia, Howard Dorgan was led to describe meeting houses and tent revivals as sites for live broadcasts; this led in turn to a discussion of “swooning in the spirit,” in which listeners fall to the ground, bodies frozen in place; this introduced the topic of carpets upon which to fall and of the need for “coverlets” to protect a woman’s modesty once she’s hit the ground — and thus were woven together everything from AM radios to portable organs to squares of velveteen. Over the years, as colleagues and students have tumbled to my predilection for religious objects, I have been helped to build up quite a collection. In addition to an heirloom Buddhist rosary of perfectly round hand-carved beads, I have vials of holy water and bags of healing soil, devotional cards, yarrow stalks, festival lanterns, shadow puppets, and, most dramatically, a ball studded with nails — used by Taiwanese shamans to beat themselves in order to draw blood for the production of amulets and medicines. I treasure my treasures, but I am sometimes troubled when students admire them. How can I help them steer clear of the tendency to either exoticize or trivialize a tradition, to caricature someone else’s faith as infantile or primitive? How are they to understand the use and misuse of the material cultural products of others’ religious imaginations? Both Freund and Strenski pose useful questions for enabling students to examine their a priori assumptions about material manifestations of religion. Popular items and religious kitsch yield different interpretive issues relative to naive art, mass consumption, humor, and cynicism. My crowded office is home to musical Marys, garish Guanyins, and Buddha squeaky toys. I have soap bars that promise to “wash away sins”; votive candles dedicated to “Our Lady of Deadlines” and “Our Lady of Perpetual Housework”; light-up devotional shrines to Ganesh and to St. Anthony; Christian “testamint” candies; heat-sensitive, color-changing yin-yang pencils; and yes, I do have a plastic Jesus “sitting on the dashboard of my car.” I am not always sure what Hindu students make of the Kali lunchbox I use to carry whiteboard markers to class, but perhaps when they notice my sparkle-red Jesus earrings — his visage embedded in acrylic that’s been poured into Diet Coke bottle caps — they can at least see that I am an equal-opportunity collector of such goods. I see these artifacts as evidence of the deeply rooted nature of religion in human culture. If the manufacture and use of tools are central to the definition of ourselves as human, it is natural for us to create tools for the expression — whether devotional, ritual, practical, or satirical — of our religious and spiritual realities, however we embrace or reject them. To leave the evidence of material culture out of the teaching of religion is, then, to eviscerate our humanity. Selected ResourcesBringéus, Nils-Arvid, ed. Religion in Everyday Life: Papers Given at a Symposium in Stockholm, 13-15 September 1993. Stockholm: Kungl. Vitterhets, 1994. Buddhanet. Provides basic introduction to structure and contents of a typical Chinese Buddhist temple. A link to www.buddhanet.net/e-learning/temple/c-temple.html provides a detailed look at a particular temple in Singapore. Although the site is still under construction, it is a fine example of a virtual lesson in temple architecture and symbolic meaning. Caldwell, Mark. “Church Signs 4 You.” Online collection of church signs (“We’re not Dairy Queen but we have great Sundays!”) and billboards (“You think it’s hot here?” -God) Chester, Laura. Holy Personal: Looking for Small Private Places of Worship. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2000. Cort, John E. “Art, Religion, and Material Culture: Some Reflections on Method.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 64 (Fall 1996). Dorgan, Howard. The Airwaves of Zion: Radio and Religion in Appalachia. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1993. Hartel, Heather. Online collection of gravestones, of which she notes a contemporary shift from images of the afterlife and reminders of the transience of this life, e.g., angels, a handshake, and various momento mori images to those that “celebrate the person’s life on earth, remembering them for the things they liked while alive,” including, it seems, Garfield and Mickey Mouse. Kieschnick, John. The Impact of Buddhism on Chinese Material Culture. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003. Knapp, Ronald G. China’s Living Houses: Folk Beliefs, Symbols, and Household Ornamentation. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1999. Lee, Jonathan H. X. “Journey to the West: Tianhou in San Francisco.” Unpublished MA thesis, Graduate Theological Union, 2002.

Material History of American Religion project. Working from 1995 through 2001, this Lilly-funded Project studied the history of American religion through examining material objects and economic themes. Although the project has concluded its work, the website has been maintained; it houses an archive of its e-journal, interviews with project participants, documents and objects collected by the project, and links to other internet resources. On the dangers of interpretation, see especially independent scholar Mary Ann Clark’s electronic journal article, “Seven African Powers: Hybridity and Appropriation,” for a discussion of the misinterpretation of devotional candles. McDannell, Colleen. Material Christianity: Religion and Popular Culture in America. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1995. McKee, Susan. Material Culture of Religion Glossary, ed. 6 (August 1998). A work of the Project on Religion and Urban Culture at the Polis Center at Indiana University-Purdue University Indiana (itself a good resource); only one section is operational at present, providing definitions of architectural terms relevant to religious sites, from abutment to zendo. Morgan, David. Protestants and Pictures: Religion, Visual Culture, and the Age of American Mass Production. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. _____. Visual Piety: A History and Theory of Popular Religious Images. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998. Strenski, Ivan. “Why It Is Better to Have Some of the Questions Than All of the Answers.” Method and Theory in the Study of Religion 14 (in press, Winter 2002). Judith Weisenfeld’s syllabus can be reviewed online at the AAR Syllabus Project: www.aarweb.org/syllabus/syllabi/w/weisenfeld/rel160/film_site.html. Teaching religion and film was also the theme for the May 1998 issue of Spotlight on Teaching, archived online at http://www.aarweb.org/. |

Vivian-Lee Nyitray is an Associate Professor of Religious Studies at the University of California, Riverside. Her research within the field of Chinese religions includes feminism and the Confucian tradition; Tianhou/Mazu studies; and the lay medical mission work of the Tzu Chi Buddhist Compassion Foundation. The Life of Chinese Religions, coedited with Ron Guey Chu, is forthcoming from the University of California Press.

Vivian-Lee Nyitray is an Associate Professor of Religious Studies at the University of California, Riverside. Her research within the field of Chinese religions includes feminism and the Confucian tradition; Tianhou/Mazu studies; and the lay medical mission work of the Tzu Chi Buddhist Compassion Foundation. The Life of Chinese Religions, coedited with Ron Guey Chu, is forthcoming from the University of California Press. The impact that first “mediated” class had on me lingers still. In other hands, such a course would have been a straightforward reading and discussion of The Analects, Ramayana, and other “great books.” For Smith, texts were more than conceptual repositories: they were manifest inspiration for music, theater, art, sculpture, architecture — a seemingly endless array of expressive cultural artifacts that could be seen, heard, and touched. Religion was neither solely cerebral nor an affair of the heart; it was thoroughly embodied; anyone who would hope to understand it had best be ready to study it in all its multifaceted glory. When the class read The Bhagavadgita, Smith brought in a set of bronze Vaishnava devotional images that he had acquired from friends in India. Oddly, at least to my eyes, each of the figures had a small piece of cloth wrapped around it. Smith explained that he’d been given the images on condition that he would treat them with respect; thus, even though the images had been cast to show the deities as clothed and bejeweled, they were not considered to be decently dressed unless real cloth at least partially enveloped them. For me, in the moment of his explanation, those small twists of cloth were suddenly and palpably imbued with the sacrality of deep devotion and respectful friendship. These images were not “gods,” but they were much more than symbols; their physical presence invoked and made warmly real the practice of bhakti devotionalism.

The impact that first “mediated” class had on me lingers still. In other hands, such a course would have been a straightforward reading and discussion of The Analects, Ramayana, and other “great books.” For Smith, texts were more than conceptual repositories: they were manifest inspiration for music, theater, art, sculpture, architecture — a seemingly endless array of expressive cultural artifacts that could be seen, heard, and touched. Religion was neither solely cerebral nor an affair of the heart; it was thoroughly embodied; anyone who would hope to understand it had best be ready to study it in all its multifaceted glory. When the class read The Bhagavadgita, Smith brought in a set of bronze Vaishnava devotional images that he had acquired from friends in India. Oddly, at least to my eyes, each of the figures had a small piece of cloth wrapped around it. Smith explained that he’d been given the images on condition that he would treat them with respect; thus, even though the images had been cast to show the deities as clothed and bejeweled, they were not considered to be decently dressed unless real cloth at least partially enveloped them. For me, in the moment of his explanation, those small twists of cloth were suddenly and palpably imbued with the sacrality of deep devotion and respectful friendship. These images were not “gods,” but they were much more than symbols; their physical presence invoked and made warmly real the practice of bhakti devotionalism. One might also move from sight to site, as it were, by engaging student attention out in the field, as contributors Ivan Strenski and Jonathan H. X. Lee suggest. Lee highlights the questions that arise as students navigate religion in three-dimensions, and he points out the rich paths that can lead onward from a single field experience. Strenski, in addition to adumbrating a theoretical perspective on the importance of material culture for the study of religion, shares the questions he has devised to guide his students’ forays into material religious spaces. In a somewhat different vein, contributor Richard A. Freund analyzes some of the pitfalls of both mis- and overinterpretation that await students and scholars alike in their encounters with the seemingly “objective” objects of biblical and rabbinical archaeology.

One might also move from sight to site, as it were, by engaging student attention out in the field, as contributors Ivan Strenski and Jonathan H. X. Lee suggest. Lee highlights the questions that arise as students navigate religion in three-dimensions, and he points out the rich paths that can lead onward from a single field experience. Strenski, in addition to adumbrating a theoretical perspective on the importance of material culture for the study of religion, shares the questions he has devised to guide his students’ forays into material religious spaces. In a somewhat different vein, contributor Richard A. Freund analyzes some of the pitfalls of both mis- and overinterpretation that await students and scholars alike in their encounters with the seemingly “objective” objects of biblical and rabbinical archaeology. Macaulay, David. Motel of the Mysteries. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1979. An illustrated tongue-in-cheek cautionary tale of future archaeologists who discover a “motel,” whose sealed chambers (“Do Not Disturb”) reveal personal altars and ablution chambers containing sacred papyrus (folded into a “sacred point”) and a “musical instrument” that relies on periodic flushes of water.

Macaulay, David. Motel of the Mysteries. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1979. An illustrated tongue-in-cheek cautionary tale of future archaeologists who discover a “motel,” whose sealed chambers (“Do Not Disturb”) reveal personal altars and ablution chambers containing sacred papyrus (folded into a “sacred point”) and a “musical instrument” that relies on periodic flushes of water.