| Disability and the Tasks of Social Justice |

![PDF-NOTE: Internet Explorer Users, right click the PDF Icon and choose [save target as] if you are experiencing problems with clicking.](http://rsnonline.org/templates/rsntemplate-smallmasthead/images/pdf_button.png) |

|

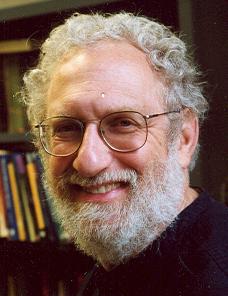

Roger S. Gottlieb, Worcester Polytechnic Institute

As is true for all great social justice movements, the full entry of people with disabilities into social life requires that we examine society as a whole and our own individual experience and beliefs, as well as take a new look at the group in question. Given the comparative newness of the disability rights movement and its many unique features, these tasks pose remarkable theoretical challenges and offer rich opportunities for teaching. 1. What is a “Disability”? Who is “Disabled”? Who Decides?Is “being disabled” a simple, natural fact about a person, comparable to their height or eye color? Or is it more socially constructed, like “being a resident of Michigan”? Some have argued for the distinction between an “impairment” and a “disability.” An impairment is some restriction on the normal functioning of a limb, organ, or mechanism of the body. A disability, by contrast, is a kind of disadvantage or restriction based in social structure and/or technological development. Five hundred years ago I, with poor vision bordering on legal blindness, would have been seriously disabled. In our society, I need merely put on my glasses to see almost perfectly. My impaired vision is, in contemporary America, no disability at all. Severe dyslexia causing an inability to read is a big deal today; but in a peasant village in which almost no one was literate, the concept of “having trouble learning to read” would not even exist. If new technologies were devised that would compensate for quadriplegia the way my glasses compensate for my nearsightedness, would people with severe spinal cord injuries cease to be disabled? Notice how key the concept of “normality” is here. We generally do not think of babies as “disabled,” even though they cannot walk, talk, or feed themselves, yet a twenty-year-old who could not do those things would be. As people approach old age, they generally become progressively less physically able, and often less mentally so. Are all old people disabled? What of conditions such as chronic fatigue syndrome, which can ebb and flow over the course of a week or month? Do people with such syndromes go in and out of the disabled group? Are seven-year-olds who cannot tolerate sitting at desks for extended periods “disabled” with Attention Deficit Disorder, or are they the victims of an educational system which stigmatized a natural and widespread need for physical movement? If a young woman with developmental delay cannot go into public alone because she lacks the social skills to know whom to trust, is the real disability hers or that of a society in which so many people are predators? 2. What is Autonomy? What is Intelligence?Clearly people with certain disabilities are highly dependent, and this, many feel, is the defining mark of their difference. Yet, while people without classic disabilities may not need Seeing Eye dogs or wheelchairs, virtually all of us in modernized societies are dependent on other people for food, electricity, housing, information, and medical care. We also need the energy provided by the sun, the action of nitrogen-fixing bacteria in the soil, food, and water. Further, at different points in our lives, our own needs may vary greatly. Break a leg or pop an eardrum and you find yourself in a radically different position than you were. At other times it may not be us who changes, but the “normality” of our surroundings. A twenty-year-old will do fine if the elevators are out of whack, but someone in their seventies might not be able to walk up fourteen floors. Given the universal fact of human dependence and the way the extent and nature of that dependence can vary over a lifetime, why is it so critically important to distinguish between the disabled and the rest of society? What is gained by making some kind of categorical separation between the two? As for intelligence, it is true that my daughter, who has a variety of distinct physical and mental special needs, cannot read the Times, do long division, or understand the nature of representative government. These are losses, and should not be either denied or ignored. Yet they are not the only kind of losses we face. Societies controlled by people of “normal” (or even “superior”) intelligence have created a world in which enormously clever technical accomplishments combine with monumental failures of efficiency, morality, and simple common sense. (One need only think of nuclear weapons and nuclear waste, gridlock, the hole in the ozone layer, or the fact that 29,000 children die each day from malnutrition or preventable diseases to see what I’m referring to.) Again, could it be that focusing on what my daughter lacks is a distraction from our own limitations? Could it be that “normal” society is riddled with such monumental obtuseness that singling out the developmentally delayed as being the ones who are deficient in intelligence is itself an act of monumental chutzpah? And perhaps a reflection of our accommodation to the social and political status quo? 3. How does “Disability” Relate to Issues of Justice and Politics of Identity?Together with other social issues, disability can be thought of in terms of justice and recognition, both the protection of rights and the granting of respect and care. Along with other groups from peasants, workers, and women to homosexuals and the colonized, those with disabilities have been marginalized, stigmatized, denied equality, and literally not seen. Because of this shared experience, both the condition of and the resistance by the disability community can be explored by applying the familiar vocabulary of democracy, rights, freedom, and respect. In this investigation it must be remembered that human identities are multiple: no one is simply a woman, a Hispanic, or blind. Each person’s identity is formed by several social identities: class and race, gender and nationality, sexuality and forms of ability/disability. Further, as white and black women have racialized experiences of patriarchy, so within the disability community there is a hierarchy in which those with only physical impairments have more status and recognition than those with mental or emotional ones. There are also (at least) two ways in which disability issues are unique, and therefore require radically new concepts and policies. First, unlike being female, African-American, or gay, having an impairment is a real deficit: there is an inability where there might have been an ability. This fact should never lead to a global devaluation of the person with the impairment, nor an unthinking acceptance that it is “smart” to make “smart” bombs or live with current pollution levels. Yet we also should not gloss over Down’s syndrome or paralysis as simply a “difference,” like being from of a different race, culture, or gender. A person who cannot walk simply should not be treated exactly like someone who can, at least when it comes to the design of a building. Second, the need of people with disabilities for extensive forms of personal care creates political issues for their caregivers, as well as those with disabilities themselves. The intense physical and emotional nature of care-giving labor, as well as its devaluation in our society, creates a socially and morally problematic situation. Those who care for the extremely dependent carry a burden far in excess of the normal subjects of political life. Because the labor in service of dependency is poorly paid and assigned to racial minorities, and because doing it well requires a unique blend of personal involvement and moral commitment, dependency workers often lack the time, energy, and resources to represent their personal interests in a public sphere designed for autonomous individuals. Thus, even political reforms based in other struggles may not be adequate to this one. For instance, although women can vote, own property, and become brain surgeons, they will lack real social equality if they are de facto expected to take primary responsibility in the care of their autistic (or some other disability) child, their father with Alzheimer’s, or their paraplegic sister. 4. How do we teach this stuff?Along with historical and theoretical writings on disability and justice, it is essential for students to get a sense of the actual life experience of those who must face these challenges. Memoirs, biographies, and films can provide some insight into the particular lives of people with disability. Strategies for developing awareness are as important as reading books and writing papers. Here are some possibilities: 1) keeping a journal in which the student pays attention to the way these issues surface in daily life, around campus, in the news — in everything from the use of “retard” as a put-down to the presence or absence of wheelchair ramps; 2) having students reflect on their own experiences of difference — how they felt “different,” “unable,” “less than,” when they were bad at sports, late to learn how to read, or lacked friends (students might write paragraphs on this topic and then the teacher may read them aloud anonymously in class); 3) having students share experiences of disability from their own lives or their families: who has a brother with Down’s syndrome, a mother with chronic fatigue, or their own unusual condition?; 4) having students “become disabled” for a day or a week: use a wheel- chair, wear a scarf over their eyes, tie all the fingers of their right hand together; 5) having students connect to someone with a serious disability and interview them, or have the person lecture to the class. In short, make it real. ReferencesCharlton, James. Nothing about Us without Us: Disability, Oppression, and Empowerment. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998. Gottlieb, Roger S. Joining Hands: Religion and Politics Together for Social Change. Cambridge, MA: Westview, 2002. Kittay, Eva. Love’s Labor: Essays on Women, Equality, and Dependence. New York: Routledge, 1999. MacIntyre, Alasdair. Dependent Rational Animals: Why Human Beings Need the Virtues. Chicago: Open Court, 1999. Mair, Nancy. Waist-High in the World: A Life among the Nondisabled. Boston: Beacon Press, 1996. Meyer, Donald J. Uncommon Fathers: Reflections on Raising a Child with a Disability. Bethesda, MD: Woodbine O’Brien, Ruth. Voices from the Edge: Narratives about the Americans with Disabilities Act. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. Scotch, Richard K. From Good Will to Civil Rights: Transforming Federal Disability Policy. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001. Shapiro, Joseph P. No Pity: People with Disabilities Forging a New Civil Rights Movement. New York: Random House, 1994. Wendell, Susan. The Rejected Body. New York: Routledge, 1996. |

Roger S. Gottlieb is a professor of philosophy and the author or editor of fourteen books on social and political philosophy, the Holocaust, religious life, and the environment. He is book review editor for Social Theory and Practice and Capitalism, Nature, Socialism, and a columnist for Tikkun.

Roger S. Gottlieb is a professor of philosophy and the author or editor of fourteen books on social and political philosophy, the Holocaust, religious life, and the environment. He is book review editor for Social Theory and Practice and Capitalism, Nature, Socialism, and a columnist for Tikkun.