| Grey Gundaker, College of William and Mary |

![PDF-NOTE: Internet Explorer Users, right click the PDF Icon and choose [save target as] if you are experiencing problems with clicking.](http://rsnonline.org/templates/rsntemplate-smallmasthead/images/pdf_button.png) |

|

|

Grey Gundaker teaches American studies, anthropology, and black studies at the College of William and Mary. Her publications include No Space Hidden: The Spirit of African American Yardwork (2004) and Signs of Diaspora/Diaspora of Signs (1998). Teaching scriptures is integral to my courses as I introduce students to foundational knowledge systems of the African Diaspora, through written, embodied, and material forms that spill over into all four foci: teaching, expressive, ethnographic, and psycho-socio-logics and politics. These forms unfold within the broader cosmologies of African Atlantic theories and practices that circulate among diverse West and Central Africans, their descendants, and the European, Native American, and Asian peoples they have encountered, often under pressured and oppressive conditions, over the past 400 years. Almost without exception these forms and the cosmologies that inform them would be unrecognizable as scripture without the intervention of ideas like those that form the ISS’s intervention into conventional academic discourses, which tend to characterize scripture as the key religious texts of major religions “of the book.” They have redirected our attention to scripturalizing processes: continuing emergent engagement and reworking through far-reaching codes, practices, and interpretive strategies of historically dominated peoples. Unlike many colleagues in this roundtable discussion, I am not affiliated with a religious studies department and none of the courses I teach — African American My teaching guides students through the first steps they must take to vernacular epistemologies (Myhre 2006) that have been marginalized by academic and usually Eurocentric grand theories of literacy, meaning, politics, and economy. These steps involve learning: 1) To see (or read) in multileveled ways that break through/move beyond sight (or) reading constrained by alien premises and a priori categories; 2) To see the ordinary and extraordinary forms scripturalizing takes; 3) To relate specific instances to wider cosmologies; and 4) To recognize the parts vernacular epistemologies and their scriptural manifestations play in orchestrating pathways toward well-lived life. Although the illustrations below are specific to the Diaspora in the southern United States, the four steps above should be useful for teaching widely disparate content because they derive from two fundamental, interdisciplinary questions: 1) How does the world work such that any given phenomenon should be the case at a particular time and place?; and 2) What do we need to know in order to understand how the phenomenon makes sense?

Lusane, a retired city worker, filled his yard with memorials to his ancestors, visual and material tributes to the first black nightspot in his county, which he and his wife ran, and “instructions” on how a mature person must be able to see in order to survive in a world that was often unjust and filled with ignorant prejudices.

BibliographyMyhre, Knut Christian. “The Truth of Anthropology: Epistemology, Meaning, and Residual Positivism.” Anthropology Today vol. 22, no. 6 (December 2006): 16–19. |

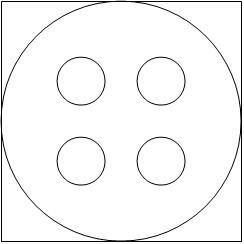

The following images illustrate the first of these steps: multileveled seeing. Thus each image involves a form of visual pun or object-word play that challenges viewers to see more than one level in order to understand them. Figure 1 “describes” this type of seeing. Figure 2 is a sign with a similar message, but different history and form. Figure 3 is a visual pun based simultaneously in vernacular epistemology and the Christian Bible.

The following images illustrate the first of these steps: multileveled seeing. Thus each image involves a form of visual pun or object-word play that challenges viewers to see more than one level in order to understand them. Figure 1 “describes” this type of seeing. Figure 2 is a sign with a similar message, but different history and form. Figure 3 is a visual pun based simultaneously in vernacular epistemology and the Christian Bible. This tall pine wears dark glasses with one lens in and one lens out, a recurring form in the Diaspora indexing sight in both the intersecting zones of spiritual and material reality. Since the glasses are themselves material and only fit two eyes, he echoed the shape below with figure-eight loops of plastic-covered antenna wires, making a sign of four-eyed vision as well. “Four-eyed” (and “two-headed”) are vernacular terms for the qualities of persons with special sight used in West and Central Africa and the Diasporic Americas. If one can see Mr. Lusane’s statement, one is also on the path to applying such sight to other situations.

This tall pine wears dark glasses with one lens in and one lens out, a recurring form in the Diaspora indexing sight in both the intersecting zones of spiritual and material reality. Since the glasses are themselves material and only fit two eyes, he echoed the shape below with figure-eight loops of plastic-covered antenna wires, making a sign of four-eyed vision as well. “Four-eyed” (and “two-headed”) are vernacular terms for the qualities of persons with special sight used in West and Central Africa and the Diasporic Americas. If one can see Mr. Lusane’s statement, one is also on the path to applying such sight to other situations. This graphic rendering of the four-eyes sign recurs in such diverse settings as the Nsibidi graphic system of Bight of Biafra peoples such as the Ejagam and Igbo, among U.S. and Cuban descendants and others with whom they have interacted, and by extension in representations of creatures such as the mudfish with spotted markings that suggest extra eyes.

This graphic rendering of the four-eyes sign recurs in such diverse settings as the Nsibidi graphic system of Bight of Biafra peoples such as the Ejagam and Igbo, among U.S. and Cuban descendants and others with whom they have interacted, and by extension in representations of creatures such as the mudfish with spotted markings that suggest extra eyes.