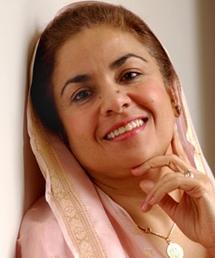

| Nikky-Guninder Singh, Colby College |

![PDF-NOTE: Internet Explorer Users, right click the PDF Icon and choose [save target as] if you are experiencing problems with clicking.](http://rsnonline.org/templates/rsntemplate-smallmasthead/images/pdf_button.png) |

|

|

Since I teach Asian religions at a liberal arts college, I have the opportunity to teach a wide spectrum of scriptures from the Indian, Chinese, and Japanese worlds, along with the Guru Granth, which is my narrow area of expertise. I have, over the years, followed three basic approaches. I will consider them in relation to the issues raise by the four foci described by Wimbush. 1) For courses at the introductory level, I give my students just a “taste” for scriptures. Scripture, especially another’s scripture, may be “too reverential,” too daunting to enter into. So I introduce Asian texts through Western fiction and poetry. We read novels like Forster’s Passage to India, Maugham’s The Razor’s Edge, Hesse’s Siddhartha, and Ondaatje’s The English Patient. Through flesh and blood protagonists these novels open up the Quran, the Upanishads, the Four Noble Truths, and Verses of the Sikh Gurus respectively; they bridge the gulf between the sacred and the everyday, between the foreign and the self. For example, an interesting exercise is a reading of The Razor’s Edge as a modern, fictional exegesis of the Katha Upanishad, the important Hindu scripture recited at death rituals. Maugham’s title and overture are a direct citation from the Katha Upanishad, but the theme of the novel bears striking parallels with the Upanishad too. Larry, the lad in Maugham’s novel from Marvin, Illinois, and Naciketas, the Brahmin boy in the Upanishadic narrative, make identical journeys: both are instructed by “death”; both give up the life of luxury, love, and money for a realization of their true self; and both go on to experience the co-presence of immanence and transcendence. Works of fiction create a sense of familiarity as Western readers can identify with the protagonists and therefore begin to feel more comfortable about entering the “sacred” texts of people from other faiths. Furthermore, such an approach creates an aesthetic delight. There is a stylistic play in interpreting the ancient story by means of another story, making the readings and rereadings very provocative. Devoid of any dull x=y equations, works of fiction provide tantalizing glimpses into scriptures; without narrowing any possibilities, they stimulate the reader’s imagination to discover the tacit connections between sacred Asian texts and modern Western novels. Similarly, Western poets like T. S. Eliot also promote a “taste” for Asian scriptures. Eliot’s musing in Four Quartets, “I sometimes wonder if that is what Krishna meant,” entices the reader to grab a copy of the Bhagavad Gita. Indeed, religion and literature are two closely interrelated aspects of the human imagination, and the approach through Western writers fosters a deep sensitivity to both these capacities. 2) At the intermediate level we do read selections from the Vedas, Upanishads, and Buddhist texts. But again, I regard scriptures as works of literature. It is not that I undermine them in any which way; to the contrary, I view sacred texts as extraordinary aesthetic and literary works, which must be recognized and analyzed and savored with our own individual senses, mind, and consciousness. It is exciting to see students contextualize the temporally and spatially distant texts in their own and different voices. Vedic hymns to Agni and Usha, the Tao Te Ching, and the Shobogenzo come out beautifully alive in their analyses and interpretations. I love when my students bring their own world into these sacred works and can take back answers and questions from them for our contemporary issues on race, gender, and class. Together we have attempted to understand symbols as constructions arising from our deep and holistic creativity as humans, which help to shatter narrow and rigid categories of exclusivism. My goal is to make Asian scriptures relevant to our lives here and now and thus introduce my Western students to different ethical models, different ways of articulating Truth and Reality — all extremely important resources for our global society. 3) At the advanced level I offer a seminar on Sikh Scripture. Here we discuss the compilation of the Guru Granth by Guru Arjan in 1604. Although the historical relationships amongst different communities in his milieu were acrimonious, the Sikh Guru did not get stuck on external differences of accents, intonations, grammar, structure, or vocabulary. Through his profoundly personal sensibility, he heard the “distinctive convergence” of languages expressed by Hindus and Muslims alike: koi bolai ram ram koi khudai — some utter Ram; some Khuda (Arjan, 885). Whatever resonated with the voice of the founder Guru Nanak — bhakhia bhau apar (language of infinite love) — Guru Arjan included it in the sacred volume for his community. Written out in the Gurmukhi script, the Guru Granth contains the poetic verses of the Sikh Gurus along with that of Hindu Bhaktas and Muslim Sufis. My overall objective is:

In the case of Sikh scripture, English has imposed his master’s voice onto the voice of the Sikh Gurus — distorting their vision of the transcendent One into a male God, reducing their multiple concepts of the Divine to merely a single concept of a Lord, and dichotomizing the fullness of their experience into Body and Soul. Such impositions, reductions, and dualizations debilitate any genuine relationship between languages. As Walter Benjamin wrote in “The Task of the Translator,” “Languages are not strangers to one another, but are, a priori and apart from all historical relationships, interrelated in what they want to express.” I share with my students the urgency to explore new ways to translate the Sikh sacred text, and thus recover the true affinity between Punjabi and English — and our common humanity. |

Nikky-Guninder Singh is the Crawford Family Professor of Religious Studies at Colby College. She enjoys teaching a variety of courses on Asian Religions, with a focus on poetics and feminist issues. Her publications include Cosmic Symphony: The Early and Later Poems of Bhai Vir Singh (2008), The Birth of the Khalsa: A Feminist Rememory of Sikh Identity (2005), The Name of My Beloved: Verses of the Sikh Gurus (1995), The Feminine Principle in the Sikh Vision of the Transcendent (1993), Sikhism: World Religions (1993), and The Guru Granth Sahib: Its Physics and Metaphysics (1981).

Nikky-Guninder Singh is the Crawford Family Professor of Religious Studies at Colby College. She enjoys teaching a variety of courses on Asian Religions, with a focus on poetics and feminist issues. Her publications include Cosmic Symphony: The Early and Later Poems of Bhai Vir Singh (2008), The Birth of the Khalsa: A Feminist Rememory of Sikh Identity (2005), The Name of My Beloved: Verses of the Sikh Gurus (1995), The Feminine Principle in the Sikh Vision of the Transcendent (1993), Sikhism: World Religions (1993), and The Guru Granth Sahib: Its Physics and Metaphysics (1981).