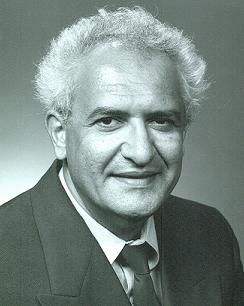

| In Memoriam: Thomas A. Idinopulos, “El Greco” |

![PDF-NOTE: Internet Explorer Users, right click the PDF Icon and choose [save target as] if you are experiencing problems with clicking.](http://rsnonline.org/templates/rsntemplate-smallmasthead/images/pdf_button.png) |

|

September 1, 1935–March 7, 2010

Relentlessly ecumenical, Idinopulos earned invitations to speak to audiences in many parts of the world. Accolades and respect came more readily abroad, it seemed, than in his native America. Mayor Teddy Kollek of Jerusalem invited him as a guest scholar to the Culture Center of the Jerusalem Foundation in 1975 and 1977. In 1981, at the invitation of Crown Prince Hassan of Jordan, Idinopulos conferred with scholars and international leaders on the future disposition of Jerusalem for Israelis and Palestinians. A Friend’s RecollectionsIdinopulos’s interest in Israel, Jerusalem, and the Holocaust was just beginning when I first met him. To me, he was — and remains — “El Greco” and I always called him that. In the beginning of January 1975, I (known as “Jake” in those days) came to work in Miami University’s Department of Religion for the winter and spring quarters. Across the hall from my office in Old Manse resided El Greco, who kept his can of Tab cooling on the window sill, who regularly ascended the stairs from the department office with his coffee cup rattling on its saucer, and who always kept his book The Erosion of Faith: An Inquiry into the Origins of the Contemporary Crisis (Crown Publishing Group, 1971) on his desk. Often while in conversation he would raise his eyebrows, erupt in laughter, or suddenly look at me very seriously, even accusingly. He played tennis in those days, a sport I regarded with disdain as too patrician. We became friends, and he and his family took me under their wing, often inviting me to their home. The two of us did not agree on much: a theologian against a historian of religions. But he, one of several University of Chicago Divinity School PhDs in the department, quickly became supportive of my future plans for study. El Greco assured me, “Chicago is the only place you can go to get a PhD.” He was right. For the next several decades, we regularly met at the AAR Annual Meetings, where he and his old Chicago friend Dan Noel (who died much too early) often roomed together. Tom and I corresponded off and on over the years. For instance, El Greco called me in November 1991 to chat, but really to find out whether I had seen, on that very day, the favorable New York Times review of his book Jerusalem Blessed, Jerusalem Cursed: Jews, Christians, and Muslims in the Holy City from David’s Time to Our Own (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1991). I had not, but I did find it. Suddenly, in the winter and spring of 2009, El Greco and I began an intense series of e-mails. I forget why, but I started it. “Jake: I am utterly delighted that you thought of e-mailing me. I bless you in His or Her name.” So starts his reply e-mail in January 2009. “Write to me. I miss you.” He had given a paper at the AAR Annual Meeting in Chicago in 2008 — a meeting I did not attend — on Joachim Wach, and he asked me to read that essay, as he planned a book of his new and previously published studies. The Wach paper came in the mail, along with three other essays, and I commented on all, for El Greco wanted to know what needed reediting. A lot did, in my mind. “El Greco: Oh boy. You’re really not wanting to enter anything postmodern, are you? More theological and stubborn than most people.” My e-mail of February 12 goes on in this vein. We were in tune on Durkheim, ritual, the social dimensions of religion, and self-centered salvation. I was an apostate Lutheran, and my proffered, solemn, official seal of the Norwegian state church certification to prove it made a certain impression on El Greco and Wayne Elzey back in 1975. They fantasized about getting me back into the Lutheran church. “Wayne and I were less interested in Lutheranism than in saving your soul” — so says El Greco’s e-mail of February 13, 2009. I had to admit that, culturally and in my bones, I was still a Lutheran. El Greco seemed like a very preachy Protestant to me, certainly not Greek Orthodox, and I told him so. Regarding his own essays, he said on February 13, “Again thanks for your probing questions....Keep this up and we can publish our correspondence as a book.” We kept going. Among other figures, we discussed Wilfred Cantwell Smith, Jonathan Z. Smith, Mircea Eliade, Paul Ricoeur, Hans Penner, William James, Rudolf Otto, and many others. In print, El Greco had been unduly harsh on Robert Segal, I felt, and I told him sternly to reedit. He assured me that they were old friends. He said, “I have to learn not to react too sharply to your riding on a high horse and looking down on us poor foot-walking romantic/religion idealists.” (April 13). We battled on “the sacred,” religious experience, idealism, and “religion” as an autonomous, analytical category. I told El Greco that he could not, in our time, seriously use the term “ultimate concern” with a straight face; that I was embarrassed by him describing his own dope experience in print; and that I rolled my eyes at his using a definition of religion found in a Catholic dictionary from 1913. In retaliation, he snidely branded me as a postmodernist, which I disagreed with, but I said that it was still necessary to understand something about that ideological position. “Do you want more of my screed?” I asked at some point in our exchanges. Yes, he did. I am sorry now that I did not go to visit him in Cincinnati in 2009. He wanted to talk and had asked me to come see him. In March 2010, Lea, his widow, included me in an e-mail announcing he had died. I treasure my memories of Thomas Idinopulos, although we sometimes shook our heads at each other, scowled, and downright offended one another. But we always reconnected, and our old friendship endured. May El Greco rest in peace. This In Memoriam piece was written by Jorunn J. Buckley. She is a historian of religions, specializing in Mandaeism, has a PhD from the University of Chicago Divinity School, and is currently an associate professor of religion at Bowdoin College. |

Thomas A. Idinopulos was a theologian with a PhD from the University of Chicago Divinity School (1965) and two MA degrees and a BA from Reed College. Most of his career, which began in 1966, was spent in Comparative Religious Studies — formerly the Department of Religion — at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. From 1999 to 2006 Idinopulos directed the Jewish Studies Program at Miami University. These positions kept him landlocked and far from his beloved Pacific Ocean. He published about 170 items, many of them essays, and twelve books, some authored, some co-edited. Three more books were in progress when he died. In 1986, The Christian Century gave Idinopulos the Associated Church Press Excellence Award.

Thomas A. Idinopulos was a theologian with a PhD from the University of Chicago Divinity School (1965) and two MA degrees and a BA from Reed College. Most of his career, which began in 1966, was spent in Comparative Religious Studies — formerly the Department of Religion — at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. From 1999 to 2006 Idinopulos directed the Jewish Studies Program at Miami University. These positions kept him landlocked and far from his beloved Pacific Ocean. He published about 170 items, many of them essays, and twelve books, some authored, some co-edited. Three more books were in progress when he died. In 1986, The Christian Century gave Idinopulos the Associated Church Press Excellence Award.